Why China Leads India in AI and Robotics Talent

While major investments are needed to expand and advance India's tech talent pool, Indian technologists abroad can help says Ravi Rao

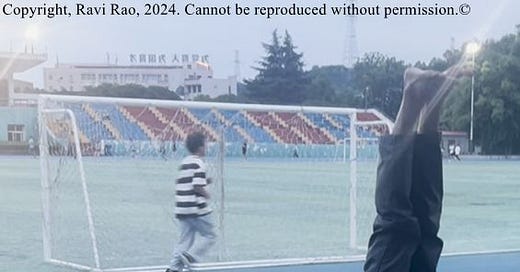

(A robotic dog in China imitating a yoga head stand. Photo Ravi Rao ©.)

By Ravi Rao*

I earned a BS in electrical engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kanpur, teach computer engineering at a university in the United States, conduct research in artificial intelligence (AI), including collaborating with some teachers at IIT Delhi, and recently spent a month teaching at a university in central China. So, based on my experience, I offer some anecdotal comparisons on the race between India and China to develop advanced talent in artificial intelligence (AI) and the related fields of machine learning and robotics.

Before my visit, I knew very little about the province of Hubei, in the interior of China, where I was to teach. The World’s largest dam, the Three Gorges dam, is in Hubei. The provincial capital is Wuhan. During my entire stay and travels in and around Hubei, I came across very few foreigners.

I taught an engineering course to a class of 120 third year students at a mid-tier Chinese university in Hubei. The students were passionate, interested and with a strong work ethic. There were no late submissions of assignments and most put in serious effort in their work, with no copying from Chat GPT and other sources. Five of the students had outstanding knowledge and curiosity and were catalysts for the other students.

Most of the students were eager to pursue Master’s or PhD studies, with AI and robotics being the top choices. The choices reflect the emphasis and spending on rapidly developing the country’s capabilities in these fields, by both the government of China and major Chinese technology companies. Also, the students are attracted by the high salaries paid to highly skilled AI and robotics talent.

Recently The Economist ran a story about how large language models are being used to make robots smarter. The companies working on the robots are well-funded American startups in the Silicon Valley. Similar advances in robotics are taking place in China on university campuses as well.

One of my students brought a robotic dog to class, made by Unitree Robotics, a Chinese manufacturer. The Go2 robot dog is priced at $1,500. In the U.S., Boston Dynamics has an entry level robot dog that costs $75,000.

One day after class, we took the robotic dog out for a walk around the campus. It did a yoga head stand, competing with my posture, much to the amusement of onlookers. The robot was an instant hit with many people taking photos and videos. Children were especially fascinated. Introducing children to such advanced products is sure to spur their interest and imagination in technology.

I saw how easy access to advanced technology products in classrooms turbo-charged student interest. Several students in my class said that, during the summer break, they will learn how to program the Go2 robot dog using advanced AI techniques, including the latest large language models as well as free opensource tools, which U.S. and other western companies put up on the web. I was surprised to find that several students had paid subscriptions to ChatGPT 4, the latest AI tool from Open AI, the U.S. company backed by Microsoft.

Based on what I saw at a mid-tier university, the study and use of AI, machine learning, and robots must be far wider and deeper at the top universities in China. Many of the advances made by Chinese companies and universities in the commercial field are featured on bilibili.com, a Chinese site which is similar to YouTube.

Bilibil shows several robotic projects completed by first and second year college undergraduate students in China. It also features a large number of university and high school competitions in robotics. The content is in Chinese, and hence technologists in the West are largely ignorant about these developments. While it is possible to use AI to translate the content into English, it requires effort.

Wuhan University, the main university in Hubei province, recently celebrated its 130th year anniversary. It has 37 schools and departments, offering more than 120 undergraduate programs, 300 plus graduate programs and more than 200 doctoral programs. It has a total student population of 56,000.

I happened to be in Wuhan during graduation week. Among the 15,000 graduating in 2024, there were nearly 3,000 PhDs mainly in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).

Even with such a large output of graduates and PhDs, the quality of education is high. Wuhan is ranked 164th in the London Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Since 2022, the Times rankings have gained a high stature after Britain began offering two and three year work visas, without a job offer, to recent graduates of foreign universities ranked among the top 50 in the world by the publication.

There are seven Chinese universities in the Times top 100 list, up from only two five years ago. In contrast, the highest-ranked Indian university on the list is the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, between #201-250. The highest ranked technology institute in India is IIT, Bombay, which comes in between 401-500.

It is sobering to compare Indian and Chinese universities even at the Asian level. Twelve universities in China are among the top 30, according to the Times rankings. The Indian Institute of Science is ranked #32, the next highest ranked Indian University is Anna University, Chennai, at #119.

The number of full-time students at the Indian Institute of Science is roughly 4,500. At Anna University the student population is nearly 13,000, less than a quarter of the number at China’s Wuhan University.

Chinese universities are rapidly improving their quality as well as creating a wide and deep pool of talent in AI, machine learning, robotics as well as in other STEM fields. This is not due to the efforts of a few Qian Xuesens – the celebrated Chinese engineer behind China’s rocket program. It is driven by government plans and funding for incremental development, by hundreds of thousands of scientists and engineers, to advance both basic and applied scientific and technologicial research.

Some of the top Chinese universities are attracting leading global STEM faculty by paying them two to three times what Harvard and Stanford pay in the U.S. In addition, Chinese faculty making major technological discoveries, including getting articles published in leading global research journals, are paid substantial bonuses.

Chinese universities are likely to exceed the prediction of a 2021 Georgetown University report. By 2025, the report stated, “Chinese universities will produce more than than 77,000 STEM PhD graduates per year compared to approximately 40,000 in the United States. If international students (mainly Indian and Chinese) are excluded from the US count, Chinese STEM PhD graduates would outnumber their US counterparts more than three to one.”

In contrast, India trails far behind in building a pool of advanced STEM talent. For instance, while the number of IITs have risen to 23, their total annual intake of undergraduate engineering students is only around 20,000. This is about twice the number of Chinese students annually enrolling in engineering courses at just one university in China, Wuhan University.

Through a combination of expanding intake at existing top ranked institutes, like the IITs, as well as setting up hundreds of new universities, India needs to rapidly expand the output of quality STEM graduates. Such a talent pool will help attract Western manufacturing and services businesses, including in AI and robotics, to set up major operations and create millions of jobs in India. The talent pool can also help tackle other important problems in India, including developing education tools in the twenty major Indian languages to improve literacy as well as basic science and math skills, which are necessary to build an advanced STEM talent pool.

But expanding and setting up new universities in India requires major investment by the Government of India, which provides most of the funding for colleges and universities in India.

One way for the Indian universities to improve their quality is to engage in more research. But this too requires major investment by the government for new labs and faculty.

At the least, even with limited resources, STEM experts of Indian origin from around the globe need to collaborate with institutes in India. Such collaboration will stimulate student interest in advanced research and techniques in India and inspire them to conduct their own research.

Since 2020, in my own small way, I am collaborating on machine learning research with some faculty and students at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. Our efforts have produced two papers published in journals and several papers presented at conferences around the world.

Very informative article...eye opener!